Betsy Ross Flag Facts - Her Life and Times

Betsy Ross - Her Life

by Jonathan Schamlzbach and Douglas Heller [This material is copyrighted by and used by permission of ushistory.org.] One year before William Penn founded Philadelphia in 1681, Betsy Ross's great-grandfather, Andrew Griscom, a Quaker carpenter, had already emigrated from England to New Jersey. Andrew was successful at his trade. He was also of firm Quaker belief, and he was inspired to move to Philadelphia to become an early participant in Penn's "holy experiment." He purchased 495 acres of land in the Spring Garden section north of the city of Philadelphia (the section would later be incorporated as part of the city), and received a plot of land within the city proper. Griscom's son and grandson both became respected carpenters as well. Both have their names inscribed on a wall at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, home of the oldest trade organization in the country. Griscom's grandson Samuel helped build the bell tower at the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall). He married Rebecca James who was a member of a prominent Quaker merchant family. It was not unusual for people in those days to have many children, so it is only somewhat surprising to learn that they had 17! Elizabeth Griscom — also called Betsy, their eighth child and a fourth-generation American, was born on January 1, 1752. Betsy went to a Friends (Quaker) public school. For eight hours a day she was taught reading, writing, and received instruction in a trade — probably sewing. After completing her schooling, Betsy's father apprenticed her to a local upholsterer. Today we think of upholsterers primarily as sofa-makers and such, but in colonial times they performed all manner of sewing jobs, including flag-making. It was at her job that Betsy fell in love with another apprentice, John Ross, who was the son of an Episcopal assistant rector at Christ Church.

Quakers frowned on inter-denominational marriages. The penalty for such unions was severe — the guilty party being "read out" of the Quaker meeting house. Getting "read out" meant being cut off emotionally and economically from both family and meeting house. One's entire history and community would be instantly dissolved. On a November night in 1773, 21-year-old Betsy eloped with John Ross. They ferried across the Delaware River to Hugg's Tavern and were married in New Jersey. Her wedding caused an irrevocable split from her family. [It is an interesting parallel to note that on their wedding certificate is the name of New Jersey's Governor, William Franklin, Benjamin Franklin's son. Three years later William would have an irrevocable split with his father because he was a Loyalist against the cause of the Revolution.]

Less than two years after their nuptials, the couple started their own upholstery business. Their decision was a bold one as competition was tough and they could not count on Betsy's Quaker circle for business. As she was "read out" of the Quaker community, on Sundays one could now find Betsy at Christ Church sitting in pew 12 with her husband. Some Sundays would find George Washington, America's new commander in chief, sitting in an adjacent pew.

Betsy went to a Friends (Quaker) public school. For eight hours a day she was taught reading, writing, and received instruction in a trade — probably sewing. After completing her schooling, Betsy's father apprenticed her to a local upholsterer. Today we think of upholsterers primarily as sofa-makers and such, but in colonial times they performed all manner of sewing jobs, including flag-making. It was at her job that Betsy fell in love with another apprentice, John Ross, who was the son of an Episcopal assistant rector at Christ Church.

Quakers frowned on inter-denominational marriages. The penalty for such unions was severe — the guilty party being "read out" of the Quaker meeting house. Getting "read out" meant being cut off emotionally and economically from both family and meeting house. One's entire history and community would be instantly dissolved. On a November night in 1773, 21-year-old Betsy eloped with John Ross. They ferried across the Delaware River to Hugg's Tavern and were married in New Jersey. Her wedding caused an irrevocable split from her family. [It is an interesting parallel to note that on their wedding certificate is the name of New Jersey's Governor, William Franklin, Benjamin Franklin's son. Three years later William would have an irrevocable split with his father because he was a Loyalist against the cause of the Revolution.]

Less than two years after their nuptials, the couple started their own upholstery business. Their decision was a bold one as competition was tough and they could not count on Betsy's Quaker circle for business. As she was "read out" of the Quaker community, on Sundays one could now find Betsy at Christ Church sitting in pew 12 with her husband. Some Sundays would find George Washington, America's new commander in chief, sitting in an adjacent pew.

War Comes to Philadelphia

War Comes to Philadelphia

In January 1776, a disaffected British agitator living in Philadelphia for only a short while published a pamphlet that would have a profound impact on the Colonials. Tom Paine ("These are the times that try men's souls") wrote Common Sense which would swell rebellious hearts and sell 120,000 copies in three months; 500,000 copies before war's end. However, the city was fractured in its loyalties. Many still felt themselves citizens of Britain. Others were ardent revolutionaries heeding a call to arms.

Betsy and John Ross keenly felt the impact of the war. Fabrics needed for business were becoming hard to come by. Business was slow. John joined the Pennsylvania militia. While guarding an ammunition cache in mid-January 1776, John Ross was mortally wounded in an explosion. Though his young wife tried to nurse him back to health he died on the 21st and was buried in Christ Church cemetery.

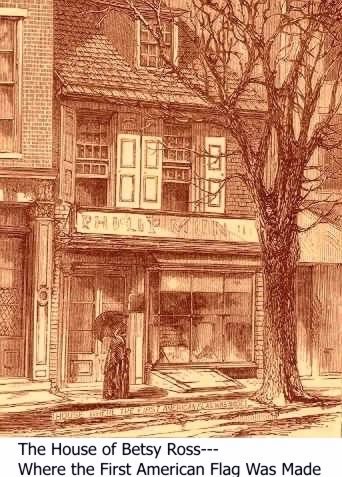

In late May or early June of 1776, according to Betsy's telling, she had that fateful meeting with the Committee of Three: George Washington, George Ross, and Robert Morris, which led to the sewing of the first flag.

After becoming widowed, Betsy returned to the Quaker fold, in a way. Quakers are pacifists and forbidden from bearing arms. This led to a schism in their ranks. When Free, or Fighting Quakers — who supported the war effort — banded together, Betsy joined them. (The Free Quaker Meeting House, which still stands a few blocks from the Betsy Ross House, was built in 1783, after the war was over.)

Betsy would be married again in June 1777, this time to sea captain Joseph Ashburn in a ceremony performed at Old Swedes Church in Philadelphia.

During the winter of 1777, Betsy's home was forcibly shared with British soldiers whose army occupied Philadelphia. Meanwhile the Continental Army was suffering that most historic winter at Valley Forge.

Betsy and Joseph had two daughters (Zillah, who died in her youth, and Elizabeth). On a trip to the West Indies to procure war supplies for the Revolutionary cause, Captain Ashburn was captured by the British and sent to Old Mill Prison in England where he died in March 1782, several months after the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia, the last major battle of the Revolutionary War.

After the War

Betsy learned of her husband's death from her old friend, John Claypoole, another sailor imprisoned at the brutal Old Mill. In May of 1783, Betsy was married for the third time, the ceremony performed at Christ Church. Her new husband was none other than old friend John Claypoole. Betsy convinced her new husband to abandon the life of the sea and find landlubbing employment. Claypoole initially worked in her upholstery business and then at the U.S. Customs House in Philadelphia. The couple had five daughters (Clarissa Sidney, Susannah, Rachel, Jane, and Harriet, who died at nine months). After the birth of their second daughter, the family moved to bigger quarters on Second Street in what was then Philadelphia's Mercantile District. Claypoole passed on in 1817 after years of ill health and Betsy never remarried. She continued working until 1827 bringing many of her immediate family into the business with her. After retiring, she went to live with her married daughter Susannah Satterthwaite in the then-remote suburb of Abington, PA, to the north of Philadelphia. In 1834, there were only two Free Quakers still attending the Meeting House. It was agreed by Betsy and Samuel Wetherill's son John Price Wetherill that the usefulness of their beloved Meeting House had come to an end. At that last meeting, Betsy watched as the door was locked, symbolizing the end of an era. Betsy died on January 30, 1836, at the age of 84.Popular Cities

Popular Subjects

EC-6 Certification Exam Tutors

Middle School World History Tutors

IB History of the Americas Tutors

Cellular Engineering Tutors

AWS Certified Solutions Architect Tutors

AP Spanish Literature and Culture Tutors

SAT Subject Test in Italian Tutors

SSAT Tutors

Middle Low German Tutors

Computational Problem Solving Tutors

Biology Tutors

Spanish Tutors

Native American Studies Tutors

Discrete Math Tutors

General Engineering Tutors

Honors Spanish Tutors

High School Political Science Tutors

R Programming Tutors

SSA - Staff Services Analyst Exam Tutors

French Tutors

Popular Test Prep