March To Quebec: Uncovering An Unsung Journalist

Anonymous Journalist on Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec: Soldier's identity uncovered after 237 years

On April 20, 1775, two brothers from Hadley, Massachusetts, William and David Pierce, joined the company of Captain Eliakim Smith that marched to Boston in response to the Lexington Alarm. Although these two brothers appear to be typical minutemen who responded to the call for volunteers, one of them was more than that. William Pierce was the author of a little known journal that has been published under the name of Anonymous. The journal relates the author’s adventures while stationed around Boston after April 20th and then gives an account of his experiences on the expedition to Quebec led by Colonel Benedict Arnold. The journal begins on September 13, 1775 and ends on January 9, 1776, shortly after the assault on Quebec on the night of December 31, 1775. To discover, after a lapse of 237 years, the identity of the soldier/ author involved in this famous and heroic expedition is, to say the least, implausible. Here, now, is the story of that discovery, first made by Steve Burk. The expedition to Quebec led by Benedict Arnold was one prong of a two pronged effort by the Continental Army to conquer Canada in the fall of 1775 [1]. Arnold led his detachment of 1100 men from Newburyport to the Kennebec River and then overland through the untamed wilderness of Maine. In Canada, the expedition proceeded down the Chaudière River to Quebec. The expedition was replete with hardships and difficulties including a hurricane, severe winter weather, leaky bateaux, and lack of food. Despite the odds, it reached Quebec in early November, although more than a quarter of its men returned south without authorization before they reached Canada. While researching the extant journals for his 2011 book on the expedition to Quebec [2], Stephen Darley found the Anonymous Journal in a fairly obscure historical and archaeological journal published by Rev. Stephen D. Peet entitled The American Antiquarian and Oriental Journal. A complete transcription of the journal appeared in the issue dated January-December, 1900 [3]. But at the time he published his book, Darley was unable to identify the name of the journal’s author. Darley did note, however, that “Prior to 1900 this journal was located in the Washington State Historical Society (WSHS). The journal was a ‘little old brown covered book’ that was presented to the historical society by Chaplain Robert S. Stubbs, who was Chaplain and Superintendent of the Seaman’s Bethel… The Chaplain apparently obtained the journal from a Mrs. Collins of Collins Landing.” From the pages of his journal it is apparent that the anonymous author was a Massachusetts soldier and that he had been in a Captain Smith’s company prior to transferring to Captain Hubbard’s company for the March to Quebec. He also mentions having a brother on the March although it is not evident whether both men were in the same company. The journal states that the author’s brother died “with fever and flux” on Dec. 28, 1775 near Quebec. Also, journal entries make clear that the author was not among the many that were taken prisoner during the Dec. 31 assault on the walled city of Quebec. These are the clues used to begin the search for the author’s identity. In telling the story of this search we hope to illustrate the nature of digital history detective work and to shine light on an American patriot whose name far too long has been locked in the dungeon of anonymity. Appendix II of Darley’s book contains a roster by company and additional information concerning those known to have participated in the March. Using this table a search was conducted for men of the same surname, without limiting them to being in the same company. And, amongst these possible brothers, instances were sought where one soldier died on the March while the other returned without having been taken prisoner. Eventually this search led to 3 Pierces (also spelled Peirce in some records [4])—David, John, and William in Hubbard’s company. John Pierce was an ensign from Worcester, MA. David Pierce is listed as having died in the wilderness on the March, while John and William Pierce are listed as “not captured”, so this fit the combination of factors being sought. But this was only a preliminary step; it was not even evident yet whether these Pierces were kin. One of these Pierces had written an Arnold Expedition journal that was anything but anonymous. Ensign John Pierce’s journal is prominently featured in Kenneth Roberts’ March to Quebec [5]. Since the Pierce name now was front and center in this search, a rereading of John Pierce’s journal was in order and, in so doing, puzzle pieces began falling into place. In a journal entry dated Dec. 30 John Pierce says [6]:“…David Peirce seemed to appearance to have been in a good way to recover and was able to walk out a broad—and was taken again all on a sudden and died in a few days he had no senses after he was taken the last time –Adiu to my Friend and Namesake.”Immediately this raises the possibility that the David Pierce above is the anonymous soldier’s brother that died Dec. 28. This possibility is greatly strengthened by the following passage from the Anonymous Journal [7]:

“Twenty-eighth December, about 2 o’clock, my brother dyed after 39 days illness with fever and flux. He seemed to be getting better and went out doors, and I think he took cold.”Clearly these two separate descriptions match up and suggest that the anonymous journalist must be William Pierce and that his brother who died is David Pierce. John Pierce does not seem to be a brother of David and William, but he does feel a connection since they have the same surname. And yet, promising as this discovery was this analysis still was in need of further verification. Since both David and William joined the army from Hadley, MA attention was directed to Pierce (Peirce) genealogy found within the History of Hadley by Sylvester Judd [8]. In the biographical section of this book (written by L.M. Boltwood) a Josiah Pierce is listed who graduated Harvard College in 1735, was a town clerk and teacher, married Miriam Cook Nov. 17, 1743, and died in 1795. The list of Josiah and Miriam’s children include this passage:

“…William, b. June 21, 1752, d. unm. (unmarried) Jan. 11, 1832, ae. 79; David, b. Sept. 27, 1754, went with Arnold to Canada, and there d. unm. Dec. 28, 1775 (bolded for emphasis)…”So this clinches that William and David Pierce were brothers and that David died on Arnold’s march on the day that the anonymous journal author (i.e., William) says his brother died, and John Pierce’s journal confirms the same. Remarkably, some 130 years after the journal was donated by a Mrs. Collins to the WSHS names can now be pinned to the anonymous Continental army soldier/author and his brother. In his 1938 March to Quebec Kenneth Roberts highlighted Ens. John Pierce’s journal as the “Lost Journal” [2], and now as revealed in these pages the anonymous author of a separate Quebec March journal turns out, ironically, to be another Pierce. With the identity of the journalist in hand, several additional clues were addressed to ensure that the case for William Pierce was sound. The anonymous journal indicates the brothers left a Capt. Smith’s company and joined Hubbard’s company for the March. From Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors in the War of the Revolution [9] the entries for both William and David begin with the phrase:

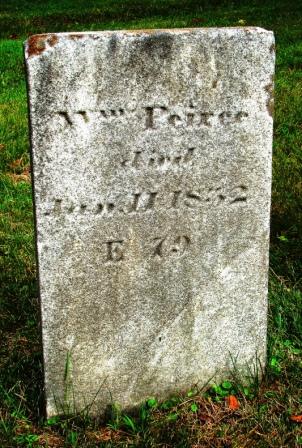

“Hadley, Private, Capt. Eliakim Smith’s co., which marched April 20, 1775, in response to the alarm of April 19, 1775…”Thus, the full identity of the Capt. Smith mentioned in the anonymous journal also is established. Further, both the preface to the anonymous journal [3] and Stephen Darley [2] note that the anonymous author writes in a surprisingly well-educated fashion for an army private at the time. However, William’s father, Josiah, was Harvard educated and a school teacher, which likely accounts for William’s writing abilities. In fact, as a prominent citizen in Hadley, Josiah Pierce was selected Oct. 3, 1774 as a delegate to the Provincial Congress at Concord [10], a meeting where the fateful decision was made to build a powder-house at Concord, leading inexorably to the Shot Heard ‘Round the World. Samuel Cook’s Revolutionary War pension application [11] of Aug. 1832 provides further confirmation of the anonymous journal’s entries. Cook lived in Hadley and was with William and David Pierce from the time they responded to the Lexington alarm, to Bunker Hill, to joining Hubbard’s company on the Quebec expedition. Cook’s application states that he and William Pierce were the only members of Hubbard’s company not taken prisoner at Quebec [12]. At the time of the assault, Cook states he was on crutches from frostbite, while Pierce was “sick and very feeble.” In full agreement with the anonymous journal entry of Jan. 3, 1776, Cook mentions that their enlistments were up and that he and William Pierce left for Montreal that day. At Montreal they re-enlisted for 3½ months, became separated when Cook contracted small pox, and ultimately met again that summer back in Hadley. There are family trees and census records listing William Pierce on Ancestry.com that some readers may wish to pursue further. Now, however, we briefly address the issue of how the anonymous journal came to reside 3000 miles from Boston in what at the time was Washington territory, and ultimately was donated to the WSHS. The preface describing the history behind the anonymous journal says it was donated by a Mrs. Collins of Collins Landing but provides no further detail. A Google search yielded a May 1, 1888 obituary in the Oregonian newspaper for Mrs. Mary T. Collins of Collin’s Landing who came to Portland with her husband from Massachusetts in the 1850’s. Then, using GenealogyBank.com, an article was found in the Morning Olympian stating that the anonymous journal belonged to Mrs. Collins’ husband and was given to Chaplain Stubbs who ultimately donated it to the WSHS. A search of Findagrave.com subsequently yielded pictures of the tombstone of William Collins (b. Feb. 21, 1813; d. Aug. 28, 1881) and Mary Torrance Collins (b. 1813; d. May 1, 1888) in the Lone Fir Pioneer Cemetery in Portland, OR. A genealogical search yielded the marriage of William Collins and Mary Torrance on June 20, 1835 near Springfield, MA, less than 20 miles from where William Pierce died 3 years earlier [13]. As of this writing, how William Collins came into possession of Pierce’s journal remains unknown; we know only of their coincidental close proximity in the 1830s. David Pierce undoubtedly lies in a shallow, unmarked and long forgotten grave in Canada. What of the anonymous author, William Pierce? He died in 1832 in Hadley. His simple tombstone in the Old Hadley Cemetery is pictured in Fig.1. However, no descendents of his will enter lineage organizations such as the DAR or the SAR based on his service, and no direct ancestors will place flowers on his grave. William, who spent his lifetime in the scenic Connecticut Valley (Fig. 2), never married and had no offspring. This patriot of the Lexington alarm, Bunker Hill, the March to Quebec, and the pivotal battle of Saratoga [14] has gone unheralded for 237 years and we hope herein to shine a light on his remarkable service and sacrifice to the American Cause.

Endnotes

- A Test of Endurance: Benedict Arnold’s March to Quebec by Stephen Darley. Vol. 5, issue 1 of Patriots of the American Revolution, 34-39, 2012.

- Stephen Darley, Voices from a Wilderness expedition: the journals and men of Benedict Arnold’s expedition to Quebec in 1775. AuthorHouse™, Bloomington, IN, 2011, 305 pp.

- “Diary of Arnold’s March to Quebec by a soldier of the American Revolution.” The American Antiquarian and Oriental Journal. Rev. S. D. Peet, Ed., Vol. 22, Chicago, 1900, 224-228. Found on Google Books.

- William and David’s surname is generally spelled Peirce, but for consistency within this article we use Pierce. Researchers must always check such variations, however.

- Kenneth Roberts, March to Quebec: Journals of the Members of Arnold’s Expedition. Down East Books, Camden, ME, 1980, 720 pp.

- Ibid, p. 703.

- in Ref.3 above, p. 227

- Sylvester Judd, History of Hadley including the early history of Hatfield, South Hadley, Amherst and Granby, Massachusetts. H.R. Huntting & Co., Springfield, MA, 1905, 504 pp. This may be found on Archive.org.

- Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, 17 vols, Boston: Secretary of the Commonwealth, 1896. Available online at www.mass.gov.

- Louis H. Everts, History of the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts, Vol.1. J.B. Lippincott & Co., Philadelphia, 1879, p.345.

- National Archives and Records Administration. Revolutionary War Pension Files, M804, Pension # W 23872. Online at www.fold3.com/image/#1|13005930.

- This statement by Cook is not accurate as evidenced by the Hubbard roster information in Appendix II of Darley’s book. However, Cook’s linkage with William Pierce and his confirmation of Pierce’s anonymous journal entries are of considerable significance to this study.

- Clifford L. Stott, the Vital Records of Springfield, Massachusetts to 1850, Vol. 3. New England Historical and Genealogical Society, p. 2552.

- William Pierce appears in the roster of participants in the battle of Saratoga compiled by NYGenWeb at http://saratoganygenweb.com/sarapk.htm.

Popular Cities

Popular Subjects

Pre-Algebra Tutors

College Computer Science Tutors

Creo Tutors

SAT Subject Test in Modern Hebrew Tutors

UK A Level Psychology Tutors

Mechanical Engineering Tutors

Literary Theory Tutors

Adobe Illustrator Tutors

Mental Math Tutors

Paleontology Tutors

Food Science Tutors

Business Administration Tutors

PMP Tutors

Quantum Computing Tutors

TOEFL Tutors

CIMA Tutors

Medical Insurance Terminology Tutors

QGIS Tutors

Physical Geography Tutors

12th Grade French Tutors