Promoting Science Through America's Colonial Press

How Ben Franklin Used His Newspaper — The Pennsylvania Gazette — to 'Popularize' An Evolving Science

Purpose

What was the role of the Pennsylvania Gazette in the 'popularization' and accessibility of science?This paper explores the dissemination and development of science in colonial America. Specifically, I examine a general periodical (or newspaper), the Pennsylvania Gazette, in the years 1729 - 1765. I impose the modern definition of science to describe a style of enlightenment natural inquiry which would include natural philosophy, naturalism, technics, medicine, and husbandry, among others. I utilize three questions:

- How did the Pennsylvania Gazette serve the interests of the public and of those doing science?

- What was the image of natural philosophy that was promoted in the Pennsylvania Gazette?

I answer these questions while detailing the commercialization of science by examining the science content in the Pennsylvania Gazette. My story includes how Benjamin Franklin utilized his newspaper to further personal goals, others' projects, and the eventual creation of modern America and modern science. I show how that utilization changed from the paper's inception up through the French and Indian War.

The paper displays the cultural embeddedness of the nascent institutions of both science and the press to inform contemporary examinations of the current manifestations of both those institutions. The core of this paper around which many insights develop is that despite the limited exposure of science in the colonial press, the newspaper was integral to the development of an experimental science, itself integral to the burgeoning capitalist society of a pre-revolutionary, colonial America.

Method

While I am admittedly examining a geographic backwater in the universe of science (not Europe), I am looking closely at the largest colonial city (Philadelphia), the most heavily subscribed colonial newspaper (Pennsylvania Gazette), and the most celebrated colonial natural philosopher (Benjamin Franklin) of the mid 1700s. To some extent this selection is based on the availability of primary and secondary material. However, examining the 'winners' of what counts as science and those better archived actors from the eighteenth century serves a purpose: I am able to detail the methods by which they achieved their success. The details include the newspaper as an instrument of consolidation for aspects of what persist as science into our own time.

For my research I surveyed all the issues of the Pennsylvania Gazette from 1728 to 1765, inclusive, using microfilm and a CD ROM product. Articles are searched for in the CD ROM product and then more closely examined in the microfilm version for accuracy. Particular periods were surveyed through the microfilm first to determine keywords and search strategies for the CD ROM product.

I examined the content of scientific articles for orientation and possible intended audience. I counted the number of articles and advertisements by various categories. I payed attention to the position of articles within the paper, and who wrote the articles and their specific and perimeter interests, such as politics, personal gain, and mercantile interests (shipping, manufacturing, agriculture, labor).

I concentrated on this time period for practical and historical reasons. Admittedly, the CD ROM product makes reading and searching the paper much easier; and it only covers up to the year 1765. However, I believe 1728 - 1765 is a critical period in the development of the general periodical. In 1728 there are only six newspapers in the colonies and this triples by 1754. The size of the Gazette triples. Also, the space given to advertisements becomes close to half the paper so it begins to more closely resemble the newspaper of today. Additionally, these years are prior to what is called the revolutionary period and a greater concentration of science articles in the general periodical are found during this time. The year 1765 is also only two years after the French and Indian War concludes, so any differences between the colonies and Britain are still minimal. The connection to British science and the Royal Society is under less of a strain than in the later period. Finally, on a more local level, the partnership between Franklin and David Hall (Franklin's editor since 1748) comes to an end in 1766 when Hall joins a separate political party.

Theory

My work is influenced and informed principally by Richard Brown (Knowledge is Power: The Diffusion of Information in Early America, 1700-1865), Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer (Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the experimental Life), Jan Golinski, Larry Stewart, and others working under what is known as SSK, or the Sociology of Scientific Knowledge (Bloor, Edge, Collins, etc) as well as Actor Network Theory (Latour, Callon, etc).

SSK argues that scientific knowledge and practice are far more socially provisioned and provisional than previously imagined. By examining laboratory settings, SSK became instrumental in reordering the authority of scientific knowledge. Social constructivism scrutinizes scientific norms: their uniqueness, degree of institutionalization, and effectiveness in motivating and prescribing action and creating facts.

In Leviathan and the Air Pump, Shapin and Schaffer create a decisive episode in empirical science: Boyle's work with the air pump. They show how open scientific knowledge is created, exhibiting various mechanisms to close debate, and noting the material and political forces on closing debates. Shapin and Schaffer show us that the political and natural philosophies Robert Boyle and his nemisis, Thomas Hobbes, reflected individual responses to social fears, desires, and contingencies. More importantly, however, the debate between these two men was a battle in what would constitute knowledge for society: what techniques and resulting data would command the polemical high ground.

Hobbes felt that experiment could never be a foundation for philosophy & a damning charge in 17th century England. Experimental facts were artificially created and needed the approval of exclusive guilds such as the Royal Society to be authoritative. To him, philosophical process should remain open to all for comprehension, provided the rules of reasoning were followed. Although mastered by only a few, the process was fundamentally unlike the expensive and mysterious experimental technology and methodology.

Boyle, like Hobbes, had concerns with the English restoration, wanted a weak church, a qualified monarchy, and rationally organized state. He differed, however, in that he wanted philosophical debates to be unambiguously settled by experiment. The results of a local experiment were to produce knowledge as universal as philosophical reasoning. This translated into a more popularly witnessed phenomenon, a more popularly determined truth, and thus potentially authorizing a more popularly determined state.

According to Shapin and Schaffer, Boyle utilized three interconnected technologies to realize his goals: material, social, and literary. The pump signified the material technology for this case. It had to work but not infallibly. The experiment's success depended on witnessing. The social technology exploited the social standing of landowners and gentlemen & as reliable witnesses (paralleling their position within the legal system). For increasing the numbers of witnesses, literary technology created a class of virtual witnesses. By writing in a particular style & detailed, naturalistic, reflexive, modest & Boyle created an instrument that puts the reader on par with those witnessing the experiment. Thus, the modern experimental method arrived; with locally controlled experimental apparatus and parameters, a cadre of experts, and the scientific report.

The results of the debate were by no means guaranteed. The three technologies might not have worked. Shapin and Schaffer's point is that Boyle's success (and science's subsequent success) has more to do with social control than with nature. In many ways, this controlled access to the production of knowledge was paralleled in the science described in newspaper.

Schaffer (1993), in "The consuming flame: electrical showmen and Tory mystics in the world of goods," examines the efforts to make natural philosophy appeal to broader audiences with the eighteenth-century electrical demonstrations of England's Benjamin Martin. These lectures were controversial, touching on "the moral ambiguity of the relation between consumer culture and natural philosophy". Schaffer uses the conflict to expound on several issues: the emergence of natural knowledge as a commodity, the boundaries between natural philosophy, commercial, and theological issues, and the perceived view of a distinction between superficial display of "the show" and "sober application." To survive, natural philosophy had to increasingly move beyond the main circles of nobility, to make the products of natural philosophy matter to the world. There were those who felt differently. Lecturers and authors then competed for audience, further solidifying the public location of knowledge production.

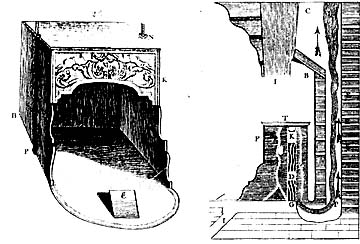

The Franklin Stove or "Pennsylvania Fireplace." Diagram at right shows currents of air during the stove's operations.

The Franklin Stove or "Pennsylvania Fireplace." Diagram at right shows currents of air during the stove's operations.Larry Stewart (1986) has noted the use of Georgian lectures by traders on the London exchange. He seeks to show why British society desired or was persuaded to have natural philosophy as an integral aspect of public life. He also argues that the different agendas vied for either public approval or private patronage. For examples, William Whiston enlisted the public in a participant fact gather exercise for determining the coast of England, while patrons 'hired' philosophers, gambling on potential insider knowledge to make a profit. The consumer revolution, with distinctive needs for utility and, at least, a perception of benefits, grew on this potential. The advertisements in newspapers demonstrate this revolution.

Yet, the rhetoric of utility was not enough. Newtonian public science needed to make its way through the larger culture of interests and philosophies. As Schaffer (1993) recalls for us the context of the religious revival movement of the time, a persistence in theocratic thinking required that the public 'witness electrical miracles.' Thus, sensational effects sold electricity and its utility with a religious flavor.

As Golinski and others remind us, however, science took the course exemplified by Lavoisier and Davy. It placed the audience in a passive role, blackboxed knowledge, and substantiated public trust by science's credibility in the marketplace more than direct public participation. It appears clearly that science's directing inner savants never really lost control. They successfully selected and controlled their audiences & elite and popular. The general periodical became a powerful tool in this effort.

Findings

The Gazette presented Science as rational, empirical, commercially viable, and opposed to superstition. The Gazette thus asked for a reading public that assimilated the epistemology of empiricism. The Gazette also made science entertaining and meaningful to attract an audience. In this way, public acceptance of scientific method and results made the newspaper critical for a developing colonial American science tied to commercial interests. Despite the importance of the audience, however, science remained aloof from the general public. And this interaction between science and the press seen in the eighteenth century continues today.

The article on the healing springs requested the reader to cast a critical eye at reports of the spring's healing power. Folk wisdom and superstition required empirical examination. That article utilized the social standing of gentlemen of science to argue its point: those with any scientific leanings would be methodologically rigorous in determining the value of the spring's healing properties. The articles on lightning, meteors, or health all strove to posit or assume phenomenological explanations.

Articles on silk worm farming, vineyards, pest control and irrigation tied themselves to the economic vitality of the colonies. The number of scientific articles that were advertisements increased over the time period we examined. The article on the healing springs benefited the submitters, Thomas and Phineas Bond, who were successful apothecary owners. The articles on subjects treated in the books sold by Franklin benefited his business.

To sell their wares, the proponents of science used that science to improve their wares' appearance. One ad notes Poor Richard as "celestially improved." A shoemaker used an engine to scientifically fit his shoes to his customers' feet. Experimenting on the White Chapel prisoners proved the effectiveness of Dr. Godfrey's cordial for bodily flux.

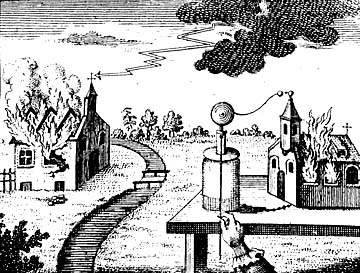

The attraction of scientific discoveries was augmented through the newspaper. Audiences were enticed to view the the 'Greenland bear' and other animals that articles described with lyrical or dramatic prose. Lightning reports became frequent and dramatic during the initial electrical years starting in 1751. Meanwhile, ads promised amazing feats by mechanical devices like the 'amazing microcosm,' or the many electricity demonstrations that complied with discovered scientific concepts.

The three technologies described by Shapin for Boyle's work with the air pump & material, social, literary & had a place in Franklin's work with electricity. The newspaper as a literary device described the equipment and publicized the results of the experiment. The utilization of the material technology of the kite and conductor, and the social technology of gentlemen and merchants of good standing, such as the scientists of France and Franklin himself, completes the triad. In that way, the facts of the experiments with lightning were solidified with a large audience. The audience became party to redefining lightning strikes as electrical phenomena. Other efforts in colonial American science utilized these three technologies to varying degrees.

Yet, little effort went into making science directly accessible through the Gazette. The style of science in the paper remained elitest, necessitating expertise, time, and resources for any in the public interested in doing science. Only a few articles, mainly the kite experiment, detailed the necessary steps to create an experimental device or experiment. In fact, the kite article only described the construction of the kite. No theory and little in the way of explanations could be found in the paper for any scientific or technical issue. It presented only what might be termed 'matters of fact' & references to scientific explanations that apparently did not need bolstering from the general periodical & and advertisements for the lectures, texts, and products of science.

Those doing science used alternative venues for communicating with each other. Franklin sent his theories on electricity to England, for example. Thus, science in the press followed market and governmental forms with a structure of specialization and representation which I term 'republican science,' a form of public science that continues today.

Bridenbaugh (1965), p. 74. Shapin and Schaffer (1985), p.189. Throughout this thesis I will be making some attempt to distinguish between 'public' and 'private' science. However, I must put these terms under erasure. Many of the participants in the constructivist approach to science that I draw upon acknowledge that science became 'public' in numerous ways during the enlightenment. Our surveys describe the work of Priestley, Martin, Kinnersley, and others to bring empirical philosophy to a broader audience. The question for the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as well as today, remains how much was and is science 'public' in that people participate in the creation of facts. Numerous scholars believe that science does not live up to its ideal and thus is not (completely) public. Golinski summarizes the ideal in Science as Public Culture:

When scientists and philosophers say that scientific knowledge is public, they seem to mean that it is accessible to all. Science has its basis in empirical facts, so anyone with normal senses can come to understand it. It is also thought that everyone can contribute to scientific knowledge, at least in principle. All claims are meant to be judged on their coincidence with the agreed-upon facts, without reference to the circumstances of their origin. Claims about the natural world become accepted scientific knowledge in a process that is supposed to be open and egalitarian. The scientific community is sometimes even taken as a model of an ideal open society.

As SSK and other scholars have shown, however, the lay person's experience of science as it impacts her/his life, rarely deals with how it is manufactured. Facts are messily created in exclusive laboratories away from public inspection, and come to public light when they are solid and beyond public critique. So 'public science,' as it should be viewed, is 'publicized science' or 'popularized science': the marketed results from those inside an exclusive 'guild' to those on the outside. Yet, the boundary between 'lay,' 'public,' or 'outside,' and 'inside' can never be completely distinct. A term of Schaffer's, meaning the many rhetorical uses to which science could be put. Stewart (1986).

Bibliography

Barrow, Robert Mangum. "Newspaper Advertising in Colonial America, 1704-1775." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, 1967.

Bridenbaugh, Carl, and Jessica Bridenbaugh. Rebels and Gentlemen: Philadelphia in the age of Franklin. New York: Oxford University Press, 1965.

Brigham, Clarence S. History and Bibliography of American Newspapers 1690-1820. Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society, 1947.

Brown, Richard D. Knowledge is Power: The Diffusion of Information in Early America, 1700-1865. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Chartier, Roger. Cultural History: Between Practices and Representations. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988.

Cohen, I. Bernard. Benjamin Franklin's Experiments. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1941.

Benjamin Franklin's Science. Cambridge. MA: Harvard University Press, 1990.

Franklin and Newton. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1956.

"Franklin's Kite and Lightning Rods." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 96, no. 3 (1952).

"Prejudice against the Introduction of Lightning Rods," Journal of the Franklin Institute (1952): 393-440.

Puritanism and the Rise of Modern Science. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1990.

Ezrahi, Yaron. "Science and the problem of authority in democracy." In Science and social structure, ed. T. Gieryn. New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1980.

Golinski, Jan V. Science as Public Culture: Chemistry and Enlightenment in Britain, 1760-1820. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

"Utility and Audience in Eighteenth-Century Chemistry: Case Studies of William Cullen and Joseph Priestley." British Journal for the History of Science (1988).

Hilgartner, Stephen. "The Dominant View of Popularization: Conceptual Problems, Political Uses." Social Studies of Science 20 (1990): 519-39.

Jensen, Arthur L. The Maritime Commerce of Colonial Philadelphia. New York: Arno Press, 1963.

Kany, Robert Hurd. "David Hall: Printing Partner of Benjamin Franklin." Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Pennsylvania State University, 1963.

Kaufer, David S., and Kathleen M. Carley. Communication at a Distance: The influence of print on sociocultural organization and change. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1993.

Kielbowicz, Richard B. News in the Mail: The press, post office, and publishing information 1200-1860. New York: Greenwood Press, 1989.

Kronick, David A. A History of Scientific & Technical Periodicals: The Origins and Development of the Scientific and Technical Press 1665 - 1790. Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, 1976.

Kronick, David. "Scientific journal publication in the eighteenth century." Papers of the Bibliographic Society of America 59 (1965): 28-44.

La Follette, Marcel C. Making Science Our Own: Public Images of Science 1910 - 1955. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Lemay, J. A. L. "Franklin and Kinnersley." Isis 52 (Dec. 1961).

Lemay, Joseph A. Leo. Ebenezer Kinnersley - Franklin's Friend. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1964.

Millburn, John R. Benjamin Martin: Author, Instrument- Maker, and 'Country Showman'. New York: Noordhoff International Publishing, 1976.

Mott, Frank Luther. History of American Magazines, 1741- 1905. New York: Appleton and Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1930. 4 vol.

Nelkin, Dorothy. Selling Science: How the Press Covers Science and Technology. New York: Freeman, 1987.

Oberg, Barbara B., and Harry S. Stout, eds. Benjamin Franklin, Jonathan Edwards, and the representation of American culture. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Olby, R. C., G. N. Cantor, J. R. R. Christie, and M. J. S. Hodge, eds. Companion to the History of Modern Science. New York: Routledge, 1990.

Pennsylvania Gazette: 1728-1752. Accessible Archives Inc. CD ROM product. Provo, Utah: FolioViews from Folio Corp.

Pennsylvania Gazette: 1728-1789. Washington, DC: Library of Congress Microfilm, 1956.

Saunders, Richard. Poor Richard's Almanac. Philadelphia: Franklin and Hall Publishers, 1733-1759.

Schaffer, Simon. "The consuming flame: Electrical showmen and Tory mystics in the world of goods." In Consumption and the World of Goods, ed. John Brewer and Roy Porter. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Schweitzer, Mary M. Custom and Contract: Household, Government, and the Economy in Colonial Pennsylvania. New York: Columbia University Press, 1987.

Shapin, Steven. "Pump and Circumstance: Robert Boyle's Literary Technology." Social Studies of Science 14 (1984): 481-520.

. "Science and the Public." In Companion to the History of Modern Science, ed. R. C. Olby, G. N. Cantor, J. R. R. Christie, and M. J. S. Hodge. New York: Routledge, 1990.

Shapin, Steven, and Simon Schaffer. Leviathan and the Air Pump. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985.

Shields, David S. Oracles of empire: poetry, politics, and commerce in British America, 1690-1750. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Stearns, Raymond P. Science in the British Colonies of America. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1970.

Footnote

Throughout this thesis I will be making some attempt to distinguish between 'public' and 'private' science. However, I must put these terms under erasure. Many of the participants in the constructivist approach to science that I draw upon acknowledge that science became 'public' in numerous ways during the enlightenment. Our surveys describe the work of Priestley, Martin, Kinnersley, and others to bring empirical philosophy to a broader audience.' The question for the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as well as today, remains how much was and is science 'public' in that people participate in the creation of facts. Numerous scholars believe that science does not live up to its ideal and thus is not (completely) public. Golinski summarizes the ideal in Science as Public Culture:

"When scientists and philosophers say that scientific knowledge is public, they seem to mean that it is accessible to all. Science has its basis in empirical facts, so anyone with normal senses can come to understand it. It is also thought that everyone can contribute to scientific knowledge, at least in principle. All claims are meant to be judged on their coincidence with the agreed-upon facts, without reference to the circumstances of their origin. Claims about the natural world become accepted scientific knowledge in a process that is supposed to be open and egalitarian. The scientific community is sometimes even taken as a model of an ideal open society."

As SSK and other scholars have shown, however, the lay person's experience of science as it impacts her/his life, rarely deals with how it is manufactured. Facts are messily created in exclusive laboratories away from public inspection, and come to public light when they are solid and beyond public critique. So 'public science,' as it should be viewed, is 'publicized science' or 'popularized science': the marketed results from those inside an exclusive 'guild' to those on the outside. Yet, the boundary between 'lay,' 'public,' or 'outside,' and 'inside' can never be completely distinct. Cited in Golinski (1992), p.6. A term of Schaffer's, meaning the many rhetorical uses to which science could be put.