Ben Franklin's Game of Love and War

The Man and the Moment

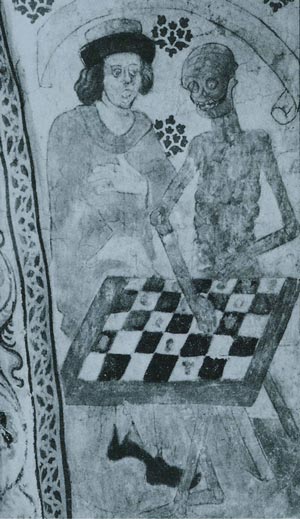

Picture Dr. Franklin seated at the chessboard in London in December, 1774 (Fig. 1). What is the 68-year-old savant thinking?

Analysis of this momentary drama depends on the historical context and the personal, social, and political forces at work at that moment. A game of chess, like a poem or painting or any creative act, is a construct embedded in history, situation, experience, ideology, etiquette, economics, law, politics, and so on. Even motionless at the table, Franklin is influenced by a web of cultural conditions and relationships, and he knows his next move will likewise influence the revolutionary changes spinning around him in the late 18th century. So, for us to see through his eyes as he sits absorbed in the position, we must reconstruct the moment through our own postmodern bifocals.Is the printer/scientist/inventor just enjoying some idle amusement? Is America's best player calculating the next moves? Is the philosopher recollecting Poor Richard's adages (Lost time is never found again)? Is the autobiographer remembering his "bold and arduous Project of arriving at moral Perfection" with its thirteen “Virtues” (6. Industry. Lose no time. Be always employ'd in something useful. Cut off all unnecessary Actions.)? Is the diplomat plotting to steer the British-American dispute into an endgame that favored the colonies? Is the ladies’ man thinking about the beautiful English lady he is playing? Or is the 18th-century wit musing on the game's political, sexual, and philosophical metaphors? Well, yes.

Alas, no record of a game or position attributed to Franklin has survived. Nonetheless, some of his letters mention chess, and he wrote two bagatelles about the game. Also, many contemporary writings to and about Franklin relate to his interest in chess, and early biographers preserved several anecdotes (some perhaps apocryphal) about him at the board. These materials, along with art and documents tracing the history and allegorical traditions of chess, form the basis for a New Historical appreciation of the influence of chess on Franklin's life and thought.

The Man and the Game

How Franklin learned the moves is unknown, but his love of games is first noted in "Journal of Occurrences in my Voyage to Philadelphia" in 1726. The entry on checkers also shows his knack of drawing moral insights from games. This passage foreshadows lessons drawn fifty years later in The Morals of Chess:

All this afternoon I spent agreeably enough at the draftboard. It is a game I much delight in; but it requires a clear head, and undisturbed; and the persons playing, if they would play well, ought not much to regard the consequence of the game, for that diverts and makes the player liable to make many false open moves; and I will venture to lay it down for an infallible rule, that, if two persons equal in judgment play for a considerable sum, he that loves money most shall lose; his anxiety for the success of the game confounds him. Courage is almost as requisite for the good conduct of this game as in real battle; for, if he imagines himself opposed by one that is much his superior in skill, his mind is so intent on the defensive part, that an advantage passes unobserved. (Hagedorn 29-30)

Given the "delight" that Franklin got from checkers, we can imagine his pleasure when he discovered chess. He must have been attracted by the richness and complexities of chess, compared to checkers, and by the closer analogy to human life, but it seems he initially did not wish to devote much time to the game. His earliest story about chess is in hisAutobiography, when he describes his study of Italian in 1733 when he was twenty-seven:

An Acquaintance who was also learning it, also us'd often to tempt me to play Chess with him. Finding this took up too much of the Time I had to spare for Study, I at length refus'd to play any more, unless on this Condition, that the Victor in every Game, should have a Right to impose a Task, either in Parts of the Grammar to be got by heart, or in Translation, &c., which Tasks the Vanquish'd was to perform upon Honour before our next Meeting. As we play'd pretty equally we thus beat one another into that Language. (Lemay and Zall 97)

Here again is Franklin's professed habit of making use of every moment for useful purposes. But we also see his irresistible attraction to the game, and his dissatisfaction with losing.

Although few players lived in the colonies, Franklin found a worthy opponent and began studying of the game. On June 20, 1752, he wrote to William Strahan, his London bookseller, to cancel an order for Philip Stamma's Essai sur le Jeu des Échecs (Paris, 1737; translated and revised as The Noble Game of Chess, 1745), one of the most modern chess manuals then available:

Honest David Martin, Rector of our Academy, my principal Antagonist at Chess, is dead, and the few remaining Players here are very indifferent, so that I have now no need of Stamma's Pamphlet, and am glad you did not send it. (Hagedorn 30)

Perhaps Franklin reordered Stamma's Essai along with other chess books precisely because he no longer had an “Antagonist.” In any case, we know he owned a small chess library by April 29, 1757, because he mentions his chess books in a letter to his wife:

Among my Books on the shelves there are two or three little Pieces on the Game of Chess. One in French bound in leather, 8vo--one in a blue Paper Cover, English; two others in Manuscript; one of them thin in Brown Paper Cover, the other in loose Leaves not bound. If you can find them yourself, send them; but do not set anybody to look for them. You may know the French one, by the Word ECHECS in the Titlepage. (Hagedorn 31)

Ralph Hagedorn, author of Benjamin Franklin and Chess in Early America, suggests, "The French book was probably an edition of Philador. . . . The English book may have been a copy of Stamma that Franklin finally received, or any of the numerous British books published prior to this date" (31). Francois-André Philador's L'Analyze des Échecs (London: 1749) would have appealed to Franklin because it contains "Rules" (i.e., strategic principles) and nine illustrative games composed for the purpose, all with sub-variations and explanatory notes. Likewise, Stamma's work would also have interested Franklin. It is a collection of one hundred parties, or chess problems, which pose middle-game positions requiring the reader to find brilliant sacrificial mating combinations--just the challenge for a player without an opponent. As for the manuscripts, Hagedorn speculates that "perhaps these notes would supply" a record of some of Franklin's own games (31). Tantalizing, but they are apparently lost. We do know that these books and manuscripts were very important to Franklin because he asked Deborah to take care of them personally.

Franklin's letter to his wife was in preparation for a voyage to London in 1757. He was no doubt aware that in England and Europe, unlike in the colonies, chess was all the rage. As Philador remarked when he began playing in the 1740s, "Chess was played in every Coffee-house in Paris" (Eales 109). The Café de la Régence was the leading chess resort in Paris, and in London it was Slaughter's Coffee House in St. Martin's Lane.

Franklin had to be looking forward to the chance to play new opponents and to enjoy the social atmosphere absent from Philadelphia. He must have believed that his brilliant mind and serious study made him "a superior player for his day" (Hagedorn 31-32). [2] He must also have recognized the importance of chess to his image as representative of the Pennsylvania Assembly because in the fall of 1757 he bought a chessboard for seven pounds (Hawke 164). [3] Such an expensive purchase seems contrary to his habit of frugality. David Hawke suggests that Franklin "indulged himself during the first month in London, as if to wash from memory the lowly life endured on the last visit" (163); however, his reasons were probably as much political as personal.

The Man and the Mission

In December, 1774, Franklin was back in London, this time as an envoy negotiating reconciliation. While there he kept a log, "An Account of Negotiations in London. . . ." In it he recounts playing with Lady Caroline Howe, sister of Lord Richard Howe, an admiral, and Sir William Howe, a general soon to lead an army to America. His reputation as a chess player must have been well known because he hears that "there was a certain Lady who had a desire of playing with me at Chess, fancying she could beat me." Although claiming to be “long out of Practice," his confidence in his playing strength is revealed by his tone (fancying).

A series of log entries (Hawke 338, 340) shows that Franklin here grasped the potential of using chess for diplomatic purposes. He records his visit to Miss Howe on December 2 (Fig. 1):

play'd a few games with the Lady, whom I found of very sensible Conversation and pleasing behavior, which induc'd me to agree most readily to an Appointment for another Meeting a few Days after; tho' I had not the least Apprehension that any political Business could have any Connection with this new Acquaintance.

His experiences with Lady Howe served him well during his next and last sojourn in Europe from 1776 through 1785, as minister to France. Despite the demands of his mission, he continued to make time for chess and for the French ladies. According to Daniel Willard Fiske, author of The Book of the First American Chess Congress, [4] Franklin "more than once visited the Café de la Régence and in all probability had the pleasure of seeing there the great sovereign of the chess men, the renowned Philidor" (335). An anecdote about one of his visits to the coffee house, related by Lafayette and preserved in a letter from Frances Wright to Jeremy Bentham, on September 12, 1821, shows that Franklin used such occasions as a stage from which to promote the American cause:Franklin quickly realized that he could use chess to conduct "political Business." His "second Chess Party with the agreeable Miss Howe" was on December 4: "After playing as long as we lik'd, we fell into a Chat, . . . partly about the new Parliament then just met." The conversation revealed that Miss Howe sympathized with the colonies and wished to prevent war. Having gained each other's trust over chess, they plotted some behind-the-scenes maneuvering. Miss Howe arranged a meeting between Franklin and Lord Howe, who also desired reconciliation. Lord Howe asked him to prepare some terms of agreement to discuss at a future meeting at Miss Howe's house, "where there was good Pretense with her Family and Friends for my being often seen, as it was known we play'd together at Chess." Though the diplomatic maneuver failed, Franklin learned that chess could be a useful negotiating tool, especially as an excuse to spend time with influential ladies.

While Franklin was negotiating in Paris, he sometimes went into a cafe to play at chess. A crowd usually assembled, of course to see the man rather than the play. Apon one occasion, Franklin lost in the middle of the game, when composedly taking the king from the board, he put him in his pocket, and continued to move. The antagonist looked up. The face of Franklin was so grave, and his gesture so much in earnest, that he began with an expostulatory, "Sir." "Yes, Sir, continue," said Franklin, "and we shall soon see that the party without a king will win the game." (Zall 144)

Several other such anecdotes portray Franklin making apropos political statements across the chessboard. Here is one from Thomas Jefferson, who was with Franklin in Paris:

When Dr. Franklin went to France on his revolutionary mission, his eminence as a philosopher, his venerable appearance, and the cause on which he was sent, rendered him extremely popular. For all ranks and conditions of men there, entered warmly into the American interest. He was therefore feasted and invited to all the court parties. At these he sometimes met the old Duchess of Bourbon, who being a chess player of about his force, they very generally played together. Happening once to put her king into prise, the Doctor took it. "Ah," says she, "we do not take kings so." "We do in America," said the Doctor. (Zall 137)

In "Anecdotes Relative to Dr. Franklin," from Memoirs of Benjamin Franklin (1818), his grandson, William Temple Franklin tells another one that would not have pleased George III:

Dr. Franklin was so immoderately fond of chess, that one evening at Passy, he sat at that amusement from six in the afternoon till sun-rise. On the point of losing one of his games, his king being attacked, by what is called a check, but an opportunity offering at the same time of giving a fatal blow to his adversary, provided he might neglect the defence of his king, he chose to do so, though contrary to the rules, and made his move. "Sir," said the French gentleman, his antagonist, "you cannot do that, and leave your king in check." "I see he is in check," said the Doctor, "but I shall not defend him. If he was a good king like yours, he would deserve the protection of his subjects; but he is a tyrant and has cost them already more than he is worth:—Take him, if you please; I can do without him, and will fight out the rest of the battle, en Républicain—as a Commonwealth's man. (Zall 131-132)

The Man and the Cultural Traditions

Perhaps to justify his passion, though supposedly to point out the practical benefits of chess, Franklin wrote The Morals of Chess in June 1779. The essay, or bagatelle, is in the medieval and Renaissance tradition of chess moralities, which drew analogies between the chessboard and the world, between the pieces and ranks in society, and between the game and life. These moralities were intended to teach lessons about social order, duty, etiquette, courtship, and the transience of life. One of the earliest examples is Dialogue of the Exchequer (c. 1177) by Richard of Ely, in which he says, "For just as on the chess-board the men are arranged in rows, and move or stand by definite rules and restrictions, some pieces in the foremost rank and others in the foremost position; here too some preside, others assist, and nobody is free to overstep the appointed laws" (Eales 50-51).

During the 13th century, clerical writers used chess as the basis for sermons, such as those compiled by the Franciscan John of Wales in the Communiloquium. One of his texts establishes the memento mori tradition in chess literature:

The whole world is like a chess-board, of which one square is white and another black, following the dual state of life and death, praise and blame. The society of this chess-board are men of this world, who are all taken from a common bag, and placed in different parts of this world, and as individuals have different names. One is called king, another queen, a third rook, a fourth knight, a fifth alphin, a sixth pawn. However, the rule of this game is such that one man takes another, and when they have finished the game, just as they come out of one place and one bag, so they are put back in one place, without a distinction between the king and the poor pawn, as rich and poor are together. (Eales 65)

In art, too, chess was treated allegorically in the vanitas or memento mori tradition. An example is The Game of Death (Fig. 2), a fresco by Albertus Pictor from the second half of the 15th century in the church in Taby, Sweden.

An example in 17th-century Dutch genre painting is Adrian van der Werff’s The Chess Players (c. 1679) (Fig. 3). Essential to this iconographic tradition is the depiction of the end of the game, indicated ironically by the proud man in the center returning the pieces to the box. The loser sitting in the dark focuses his gaze on his opponent and raises his hands in a gesture of despair as if to admit that he is unbeatable, but also perhaps symbolically in recognition of the inevitability of death (Watkins 358-359). The victor seems unaware of the transitory nature of his glory. The dog doesn’t care about the human drama.

A second allegorical theme related to chess is a comparison of the contest to the game of love. Couples were often portrayed in stylized romantic groves reminiscent of Paradise, as in The Garden of Love (c. 1445-50), a copperplate engraving by the German Master E.S. (Fig. 4). A chess game is at the center of an enclosed garden occupied by three amorous couples.

A similar 15th-century scene is pictured in part of a wall hanging also entitled The Garden of Love (c. 1470), in which the woman is portrayed as the Queen of Love (Fig. 5).

A 17th-century example, again from Dutch genre painting, is Cornelis de Man's Chess-players (c. 1670). It offers an intimate glimpse of chess being played in a patrician home (Fig. 6). The rich interior, the chessboard-like tiled floor, the man's satin jacket, and the woman's velvet housecoat attest to their prosperity. Even the cat basking by the hearth seems content with the comfortable domestic atmosphere. Yet within this peaceful interior a battle of the sexes is climaxing. The woman is making an unexpected move that alarms her partner. By looking back at the viewer with a smile and pointing, she seems to engage the observer and the cat in a conspiratorial spirit. The painting could suggest the triumph of love attained by the queen, a symbol of female dominance (Watkins 244) in this game of cat and mouse.

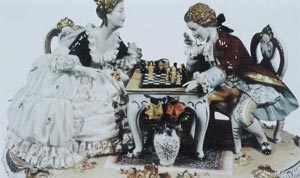

The analogy between chess and amorous play was still a tradition in the 18th century, as shown by a c. 1790 Ludwigsburg porcelain figure of a lady and her gallant at play (Fig. 7).

Elements from these cultural traditions appear not only in Edward Harrison May’s painting of Franklin playing chess with Lady Howe, but also in Franklin's two main texts on chess.

The Man and the Bagatelles

Franklin printed The Morals of Chess in Passy in 1779, and after returning to America he submitted it for the December 1786 Columbian Magazine (Vol. I, No. 4). It was immediately popular. At least thirteen reprints and translations appeared by 1800. It starts by stating that it was "written with the view to correct (among a few young friends) some little improprieties in the practice of it, shows at the same time that it may, in its effects on the mind, be not merely innocent, but advantageous, to the vanquished as well as the victor" (Posthumous and other Writings, vol. 1, 242-43). As chess etiquette, Franklin disapproves of disturbing an opponent by singing, whistling, looking at your watch, reading a book, tapping your feet, or drumming your fingers. He says not to deceive your opponent by pretending to have made a bad move or saying you have lost the game, and gloating is bad manners. Clearly, Franklin understood human nature. Walter Korn, in America's Chess Heritage from Benjamin Franklin to Bobby Fischer, calls the essay "an American constitution for chess and its own pursuit of happiness" (6). Franklin explains the central metaphor:

The game of chess is not merely an idle amusement. Several very valuable qualities of mind, useful in the course of human life, are to be acquired or strengthened by it, so as to become habits, ready on all occasions. For life is a kind of chess, in which we have often points to gain, and competitors or adversaries to contend with, and in which there is a vast variety of good and evil events, that are, in some degree, the effects of prudence or the want of it. By playing at chess, then, we may learn, Foresight . . . Circumspection . . . Caution . . . [and] the habit of not being discouraged by present bad appearances in the state of our affairs, the habit of hoping for a favorable change, and that of persevering in the search of resources. (Posthumous and other Writings, vol. 1, 243-44)

Figure 7. A Ludwigsburg porcelain figure (Finkenzeller 120)

One friend Franklin had in mind when he wrote The Morals of Chess was Madame Anne-Louise Brillon de Jouy, his neighbor and the attractive wife of a man thirty years older than she. In the letter he sent to her with a copy of his first edition, he says,

I inclose the little pieces that my most dear friend has done me the honour to ask for. The one on the Game of Chess must be dedicated to her, the finest advice it contains being drawn from her generous and magnanimous way of playing, which I have so often witnessed. (Hagedorn 84)

He had met Madame Brillon in 1777, and they soon became close friends. On July 30, 1777, she sent him the following note:

It is a real source of joy for her to think that she can sometimes amuse Mr. Franklin, whom she loves and esteems as he deserves; still, she is a little miffed about the six games of chess he won so inhumanly and she warns him that she will spare nothing to get her revenge. [5] (Lopez 35)

He gave her every chance to get her revenge, visiting her once or twice a week during his first half dozen years in Passy. On one evening in particular Franklin and another neighbor played chess in her bathroom while she soaked in her tub under a wooden plank, as was the French tradition. The next day he sent her an apology:

On reaching home I was surprised to find that it was almost eleven o'clock. I fear that by forgetting all else in our too great absorption in the game of chess, we have greatly incommoded you by detaining you so long in the bath. Tell me, my dear friend, how you are this morning. Never hereafter shall I consent to begin a game in your bathroom. Can you forgive me this indiscretion? (Hagedorn 36-37)

This anecdote, along with what she called "the sweet habit I have taken of sitting on your lap, and your habit of soliciting from me what I always refuse" (Lopez 59), suggests that Franklin did not forget “all else” when he played chess.

As a result of high living and little exercise, Franklin developed gout, arthritic joint inflammation. In the fall of 1780, at seventy-four, he suffered an extremely painful attack. In her typically teasing style of flattery and mockery that Franklin found so irresistible, Madame Brillon sent him a verse dialogue, Le Sage et la Goutte, in which the ailment, personified as Madame la Goutte, chides: "You like food, you like ladies' sweet talk,/ You play chess when you should take a walk,/ You like wine. This may seem good and well,/ But your fluids meanwhile rise and swell.” Franklin wrote back, "When I was a young man and enjoyed more of the favors of the sex than I do at present, I had no gout. Hence, if the ladies of Passy had shown more of that christian charity that I have so often recommended to you in vain, I should not be suffering from the gout right now" (Lopez 78-79).

His more fully developed literary response was the bagatelle, "Dialogue Between Franklin and the Gout," dated "Midnight, October 22, 1780." In it he asks why Madame Gout tortures him, and her response shows his awareness that his preoccupation with the game was unhealthy. The self-satire admits that he deserved it:

Gout. . . . What is your practice after dinner? . . . yours is to be fixed down to chess, where you are found engaged for two and three hours. This is your perpetual recreation, which is the least eligible of any for a sedentary man. . . . Wrapt in the speculations of this wretched game, you destroy your constitution.(Hagedorn 37-38)

Madame Gout recommends the pleasures and benefits of taking after-dinner walks in the gardens, "But these are rejected for this abominable game of chess."

Franklin confesses she is right and swears, "Oh! Oh!—For Heaven's sake leave me! and I promise faithfully never more to play at chess, but to take exercise daily, and live temperately." Madame Gout suspects that "after a few months of good health, you will return to your old habits." She understood his incurable passion for the game. [6]

The Man and the Metaphor

For the rest of his life, Franklin continued to use apt allusions to chess. Like all his anecdotes and aphorisms, his wise metaphorical references to chess still apply to today. For example, when Madame Brillon scolded him for not telling her of Washington's victory at Yorktown, he wrote back on Christmas Day, 1781, explaining why he had not boastedMission Accomplished:

Knowing that war is full of changes and uncertainty, in bad fortune I hope for good, and in good I fear bad. I play this game with almost the same equanimity as when you see me playing chess. You know that I never give up a game before it is finished, always hoping to win, or at least to get a move, and when I have a good game, I guard against presumption. (Lopez 110)

Franklin knew better than to expect certainty and perfection in human affairs. Written in Philadelphia as Congress struggled to ratify the Constitution, his final mention of chess shows his political experience and wisdom. In a letter to Pierre-Samuel du Pont de Nemours on June 9, 1788, Franklin leaves some advice that still holds true under Obama: "But we must not expect that a government may be formed, as a game of chess may be played, by a skilful hand, without a fault" (Hagedorn 41).

For Franklin, chess was not only an "idle amusement" and a bit of dalliance, but also a literary inspiration, a political stage, a model for law and government, a reflection of human nature, and a reminder of mortality. Perhaps also it was an enclave of order amid the chaos of the 18th century, a refuge from the cares of his busy life. Perhaps in chess Franklin found a sanctuary where the mind could momentarily rise above our tragic flaws and find moves of perfect reason and pure imagination. [7]

Works Cited

Eales, Richard. Chess: The History of a Game. New York and Oxford: Facts on File Publications, 1985.

Finkenzeller, Roswin, Wilhelm Ziehr and Emil M. Buhrer. Chess: A Celebration of 2000 Years. Toronto: Key Porter Books, 1989.

Fiske, Daniel Willard. The Book of the First American Chess Congress. New York: Rudd & Carleton, 1859.

Golombeck, Harry. Chess: A History. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1976.

Granger, Bruce Ingham. Benjamin Franklin: An American Man of Letters. Norman: U. of Oklahoma Press, 1976.

Hagedorn, Ralph K. Benjamin Franklin and Chess in Early America. Philadelphia: U. of Pennsylvania Press, 1958.

Hawke, David Freeman. Franklin. New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

Korn, Walter. America’s Chess Heritage from Benjamin Franklin to Bobby Fisher—and Beyond: A Chronicle of America’s Contribution to the Game of Chess. New York: David McKay Co., 1978.

Lemay, J. A. Leo and P. M. Zall, eds. The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, a Genetic Text. Knoxville: U. of Tennessee Press, 1981.

Levitt, Gerald M. The Turk, Chess Automaton. McFarland, 2000.

Lopez, Claude-Anne. Mon Cher Papa. Franklin and the Ladies of Paris. New Haven and London: Yale UP, 1900.

McCrary, John. “Chess and Ben Franklin—His Pioneering Contributions." Online.

Posthumous and other Writings of Benjamin Franklin, . . . Published from the Originals, by His Grandson, William Temple Franklin. 2nd ed. London: Henry Colburn, 1819.

Saidy, Anthony and Norman Lessing. The World of Chess. New York: Random House, 1974.

Tuckerman, Henry T. Book of the Artists: American Artist Life Comprising Biographical and Critical Sketches of American Artists: Preceded by an Historical Account of the Rise & Progress of Art in America. 1st published 1867. Reprinted New York: James F. Carr, 1966.

Watkins, Jane Iandola, ed. Masters of Seventeenth-Century Dutch Genre Painting. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1984.

Zall, P.M. Ben Franklin Laughing: Anecdotes from Original Sources by and about Benjamin Franklin. (Berkeley: U. of California Press, 1980).

Endnotes

[1] Edward Harrison May (1824-1887) was born in England, spent his childhood in New York, took up painting under Daniel Huntington, and “entered Couture’s studio in Paris, in 1851" (Tuckerman 502). In a biographical sketch of May in1867, Henry Tuckerman mentions May’s “Franklin playing Chess with Lady Howe, painted for an American, Mr. Farnham" (502). Mr. Farnham was most likely Daniel Farnham (1799-1881), son of Benjamin Farnham, who fought in the American Revolution (California Genealogy, Yolo County Biography, Erastus Sylvester Farnham. Online).

The title used by Henry Tuckerman in 1867, Franklin Playing Chess with Lady Howe, seems more likely than the improbable event of Lady Howe Checkmating Benjamin Franklin, as this painting is referred to in later sources, or Lady Howe faisant mat Benjamin Franklin, as seen sometimes now on the internet.

When it was painted is also an unresolved question. No scholarly reference book lists the information. Under some of the copies online they say 1867, but only one site gives a source. The image on Google from www.jmrw.com/Chess/Tableau_echecs refers to Les Échecs Roi des Jeux, Jeu des Roi by Jean-Michel Péchiné (Gallimard: Nov. 4, 1997), but Péchiné’s source is unknown, and the match to the publication date of Tuckerman’s book raises more questions.

The truth about its provenance must be with the painting itself, but even its whereabouts is a mystery. Saidy and Lessing in 1974 attribute it to the Manson Collection at Yale University Art Gallery (248), but an online search of the Yale collection yields one result for Edward Harrison May (George Washington and Miss Custis) and no Manson Collection.

The facts about this painting need to be researched further, but they are not essential to understanding Ben Franklin.

May’s composition has many of the elements of chess traditions in art. The square floor tiles suggest a position on a chess board. The servant putting away the pieces indicates the end of the game, a symbolic reminder of death (momento mori) and the transience of glory. Lady Howe is looking rather proud of herself (vanitas). Franklin is playing with “equanimity," as he once described himself: “I never give up a game before it is finished, always hoping to win, or at least to get a move." The dog doesn’t care about the battle of the sexes being played at the table.

[2] For an assessment of Franklin’s playing strength, see “Chess and Ben Franklin—His Pioneering Contributions" (Online), by John McCrary, past president of the United States Chess Federation. McCrary concludes that “he was an above-average player, but not at the level of the top players of his day . . . [and] not of Master strength by modern standards." Likewise, Fiske, president of the First American Chess Congress in 1859, believed Franklin was “among the best of the second class" (339).

[3] Franklin’s chess set is one of over 250 artifacts in a traveling library exhibit called Benjamin Franklin: In Search of a Better World, touring 31 states until July 2011. The French Regency pieces, probably made from fruit wood, are pictured on The Benjamin Franklin Tercentenary website with the annotation, “The 18th-century set descended in his family with the history of having belonged to him."

[4] Franklin has always been celebrated as the founding father of American chess. On October 6, 1857, opening ceremonies for the First American Chess Congress took place on Broadway in New York in a hall decorated like a chess shrine. “At the east end of the main Hall, a room eighty feet in length, was a slightly raised platform, over which hung the American flag, draping the bust and bearing the name of Franklin, the first known chess player and chess writer of the New World" (Fiske 68). At the dinner on October 17, the table was adorned with chess ornaments, including “statues of Franklin in ice" (96), and the menu included “Pudding à la Franklin" (97).

[5] The evidence in this letter contradicts the online rumor “that Franklin received odds from Madame de Brillon regularly, and lost regularly" (Kibiter’s Corner, chessgames.com, Jan. 26, 2007). Daniel Fiske discounted the rumor at its source in 1859: “In the Palaméde it is said that Franklin, while in Paris, used to encounter a lady, Madame de Brion [Brillon?], who was able to give him odds. But no authority is given for this assertion" (338). Le Palamède, published in Paris from 1836-39 and 1841-47, was the first magazine devoted to chess.

[6] Still playing in 1783, Franklin lost in the Café de la Régence to The Turk, the famous chess-playing automaton, later proven a hoax. His grandson William wrote, “He was pleased with the performance of the Automaton," but some reasonable skepticism is suggested by the presence in Franklin’s personal library of Philip Thicknesse’s The Speaking Figure and the Automaton Chess Player, Exposed and Detected (London, 1784) (Levitt, 27-29).

[7] In 1999 Franklin was inducted into the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame in Miami, Florida.